For anyone who works in marine tech, especially subsea, it doesn’t take long for you to hear or see AUV, UUV, ROV or any number of other initialisms (no not acronyms) ending in ‘v’. All of these abbreviations refer to classes of underwater vehicles. I often hear folks using these terms interchangeably, but one is not necessarily the other. Read on to learn which is which.

The Ocean Vehicle Taxonomy

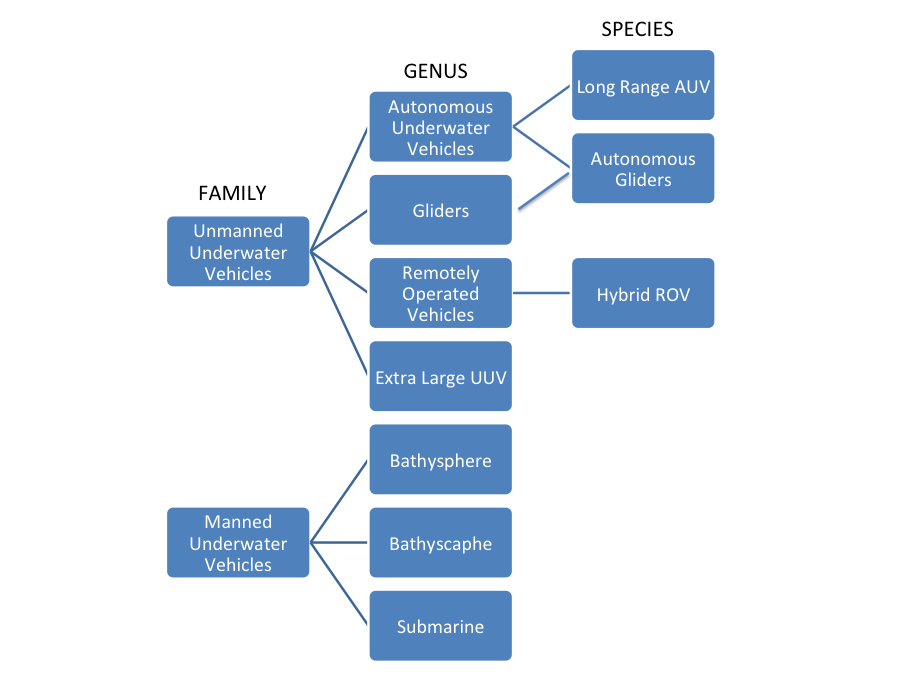

When describing underwater vehicles it helps to use the family, genus, species taxonomy. Let’s start at the highest level and work done. Subsea vehicles come in one of two flavors: manned or unmanned (people on board or not). These are our two families.

Manned Vehicles

Let’s touch on the people-carrying vehicles first. In the early days, the simplest way to deliver someone to the seafloor was to shove them in a steel sphere with a small window and lower them underwater with a cable attached to a ship. Sounds fun right? If it’s spherical in shape (the most resistant to deep sea pressure) it’s called a bathysphere, this is our first genus. If it’s not spherical, then it’s just a manned submersible. A well-known example of this would be ALVIN which was used to discover Titanic.

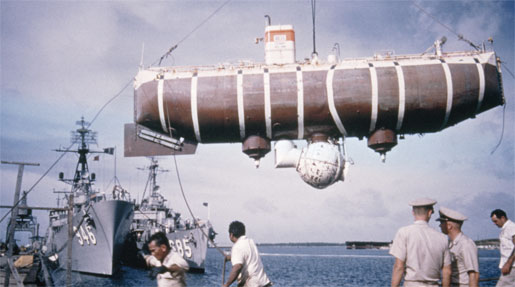

A different type of manned submersible is the bathyscaphe which is self-propelled and free-diving (unlike the bathysphere which is tethered to a vessel). The Trieste is an example of a bathyscaphe from the 1960s that descended into the Marianas Trench to a depth of almost 11,000 kilometers with two crew on board. Perhaps we should call it Bathyscapheia Triesteia.

We’ve always known that using people to explore places as inhospitable as the Marianas Trench was crazy. It’s simply too difficult to develop vehicles that can go that deep while keeping their crews alive and safe for long periods of time. If you take people out of the equation however, that changes the problem. Enter the unmanned underwater vehicle family.

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles – UUVs

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles, or UUVs, are vehicles that do not have a human on board but are controlled remotely from ship or shore via cables, wireless communication, or sometimes not at all. They come in a range of shapes and sizes, from dozens of feet long and weighing as much as a school bus, to little foot-longs weighing as much as watermelon. This family of vehicles changed ocean exploration, allowing us to probe deeper, further, and longer than we ever could with manned vehicles.

There are several different genera of UUV, including Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), Gliders, or even the Extra Large UUV (XLUUV). In this half of the family tree the branches sometimes overlap, possibly due to some interspecies mingling.

ROVs are vehicles that have a direct link to their controller via a tether. Navigation and control of the vehicle is handled in real-time by a human operator which allows for precise manipulation of the vehicles appendages (if equipped) to grab objects or thrusters to squeeze into tight areas. Since these vehicles are connected to the surface with a tether, power and communications are rarely an issue.

ROV in Action (Offshore Magazine)

ROVs are controlled in real-time by operators on vessels. (Oceaneering)

An ROV being recovered (Oceaneering)

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles

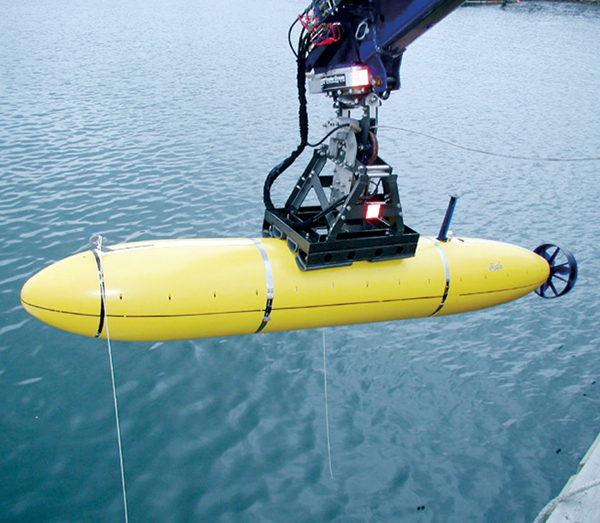

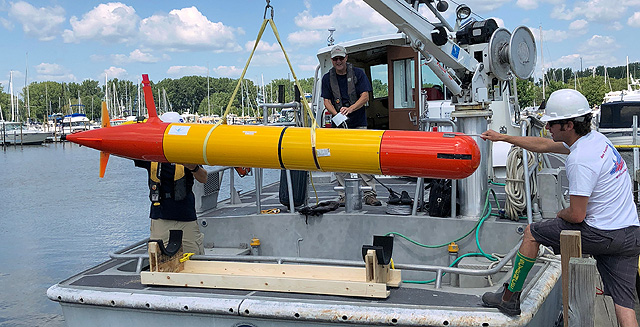

AUVs are self-propelled free-diving vehicles where navigation and control is handled on-board the vehicle. There is some debate about what it means to be truly autonomous, but in general it means that the system can respond to its environment without human intervention. An example of this would be if the vehicle could sense a hazard, such as an oncoming ship, and navigate out of the way on its own. Without a tether, power and communications become more important for AUVs: they must carry sufficient energy onboard to last for the mission (usually via batteries) and communications are usually restricted to when the vehicle can surface and make connection with a ship or satellite.

An AUV (MBARI)

Another AUV, built by Bluefin Robotics (AUVAC)

The range and duration of the AUVs can be problematic, especially when operators want to keep them out at sea for long periods of time. This lead to the creation of a new species of AUV that can stay out at sea longer than an average AUV, aptly named the Long Range AUV, or LRAUV. In most cases these are just big AUVs with more battery power.

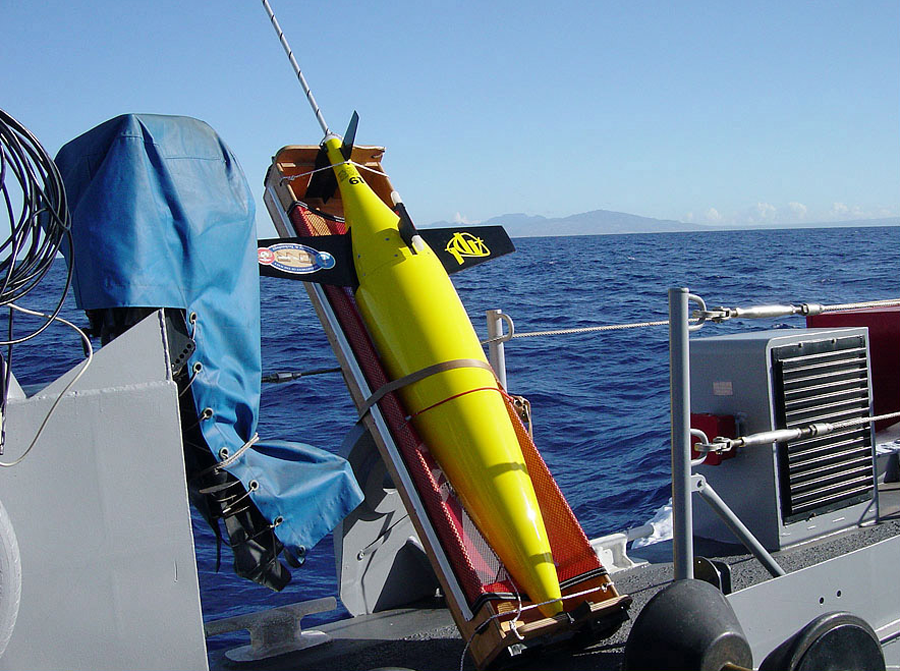

Another genus of UUV are the Gliders. These vehicles can also be referred to as Autonomous Undersea Gliders, but their level of autonomy is usually less than that of an AUV. Given how much this industry loves abbreviations, I have no idea why AUG didn’t catch-on. Gliders are designed for long duration deployments and cover large distances using power minimizing propulsion methods like buoyancy engines. They traverse entire oceans while cutting a saw-tooth pattern through the water column, resurfacing periodically to communicate with satellites and transmit data back to shore. Given the significant amount of time spent on deployment these vehicles are engineered to use as little energy as possible.

The Sea Glider (UW-APL)

The Sea Glider’s typical path (Kongsberg)

A final type of genus I’ll highlight here is Large UUV (LUUV) and the Extra Large UUV, or XLUUV. These are terms that gained traction in the defense world with the introduction of the Boeing Echo Seeker and Boeing Echo Voyager respectively. Boeing’s newest vehicle, the Orca is over fifty feet long and pretty much an unmanned submarine. These vehicles have powerful propulsion and significant range. Boeing claims they are autonomous, but for whatever reason their sticking with the UUV classifier.

The Underwater Vehicle Family Tree

So there you have it. AUVs and ROVs are different genuses of the UUV family. AUVs can respond to their environment and make decisions on the fly without a human operator, ROVs cannot. Gliders could be an AUV, it just depends on their control system. An XLUUV is just a big UUV, though it could also be an AUV. There are several other ways to classify underwater vehicles, such as by propulsion type or hull diameter, but we’ll save that for a deeper discussion. As the evolution of undersea vehicles progresses we’ll have to add some more branches to the tree, but that’s enough initialisms for today.