This is part two in a three part series investigating ocean plastic pollution. Part one laid out the scale and complexity of the problem. This article will compare the different technical solutions based on their respective effectiveness and costs.

Upstream and Downstream

Ocean plastic is extremely hard to collect and sadly there is little financial incentive to do so. In fact, it’s usually a money-losing proposition. That’s probably why there are so few pieces of tech that are focused on this problem. As best I can tell there are three different tech-focused solutions for ocean plastic pollution: the Sea Bin Project, The Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore’s Mr. Trash Wheel, and the Ocean Cleanup Project. None of these companies claim that their technologies are a silver bullet, but they can certainly be part of the solution.

When it comes to removal of trash from the ocean, there are really two places that you can focus your efforts: downstream or upstream. These terms are a little subjective, but for the purposes of this article downstream efforts remove trash that has already entered the oceans or other major bodies of water. Upstream efforts are those that seek to prevent trash from ever reaching major bodies of water at all. Upstream removal is more efficient since the trash is generally more concentrated in one area and less degraded compared to collection far out at sea, but both methods have their merits.

The Sea Bin Project and Baltimore’s Mr. Trash Wheel are two pieces of tech for upstream trash removal. Both serve the same purpose, but their methods of collection are unique. The Ocean Cleanup Project is the only example of a downstream device that I could find, and for good reasons as we’ll get into later. Now, onto the tech!

Mr. Trash Wheel

The Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore’s Mr. Trash Wheel is manufactured by Clearwater Mills. In simplistic terms it’s just a simple ancient-Greek-style water wheel that is mechanically linked to a conveyor belt which scoops floating trash off the water’s surface.

The floating device is strategically positioned in the center of a river where it meets the inner harbor of Baltimore. Extending out to either side of the device like giant antennae are floating booms that funnel the floating trash into the ‘mouth’ of the device. Near the mouth there are several rows of mechanical rakes that sift through the floating debris and drag it onto a slow-moving conveyer belt.

The water wheel on the side of Mr. Trash Wheel is typically powered by the flow of the passing river water. If river currents are not strong enough, a 2.5 kW solar photovoltaic array on top of the device powers some pumps that are used spray water on the paddles and keep the wheel spinning. The water wheel is mechanically linked to the conveyor belt, and as the wheel spins the conveyor rotates. Ever so slowly the conveyor lifts the trash out of the water and then deposits it into a dumpster on the back end of the device. Once the dumpster fills up it is towed away by a boat to a waste-to-energy facility. You can watch a video of Mr. Trash Wheel in action here.

It’s a simple design and it has been doing a great job. Since it was deployed in May 2014 it has prevented approximately 1.6 million pounds of debris from entering the Ocean. In one single day after a heavy rainfall it removed an impressive 38,000 pounds. These weights include organic matter like tree limbs, leaves, and dead fish, but also a good deal of plastic bottles, cups, and plastic bags. This makes one wonder why Baltimore has so much trash in the water, but we’ll save that for another day. You can help fund Mr. Trash Wheel and future projects like him by buying an awesome t-shirt.

The Seabin Project

The Seabin is a trash removal device that is produced by an Australian startup company called The Seabin Project. Unlike Mr. Trash Wheel that lifts the floating debris out of the water on a conveyor, this device sucks the floating debris down into a submerged container.

The Seabin looks very similar to a submerged trashcan. The actual bin is attached to the bottom of a two-meter-long ‘L’-shaped metal bracket that is used to attach the contraption to a dock or boat. At the bottom of the bin is a submerged pump. Fitted inside the bin is a removable fine mesh insert that traps the trash.

When the Seabin is installed, the top of the container sits just below the surface of the water. Once the submerged pump is switched on it draws suction through the top of the bin and the surrounding surface water and debris is pulled inside. The fine mesh separates out the trash from the water just like an oversized filter. Once the mesh liner is filled with trash someone must come by to empty it.

Not only can the Seabin remove cigarette butts, plastic bags and bottles, but it can also remove very fine particles like microplastics and even oil from the water in which operates. Another advantage of this system is that it’s relatively hidden since most of it is underwater. Out of sight, out of mind.

Seabin devices are smaller than Mr. Trash Wheel and so clearly their ‘trash capacity’ is nowhere near as large, only about a 1,000 pounds a year according to the manufacturer. That may not sound like much, but when many of these are deployed in a marina they can start to do some serious damage to the trash problem. Someone just needs to empty all of them bins.

Ocean Cleanup Project

Our last device is the Ocean Cleanup Project. This device was dreamed up by a young Boyan Slat and promoted as a way to rid the ocean of plastic and has received plenty of media attention, and funding. This is the only downstream device being seriously developed of which I am aware and it is being designed for deployment in the gyre at the heart of the North Pacific Ocean, or colloquially known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. If it proves successful, the goal is to deploy many more devices like it in the other four major ocean gyres.

The Ocean Cleanup device consists of long floating barriers that fan out like outstretched arms with a slight concavity. The barriers are comprised of a string of modular rubber pontoons linked together like a big marine sausage. Attached to the underside of each pontoon is a barrier, kind of like a floating fence.

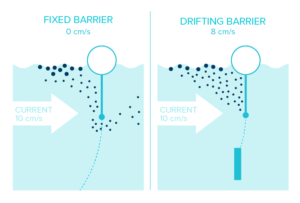

The original design for this system called for a 62-mile-long array of floats [5] moored to the sea floor, but this has since been revised down to a more modest 0.6-miles-across passive free-floating system. The latest design is not tethered to the ocean bottom but instead drifts with the currents in the gyre. However, it drifts at a reduced rate (about 20% slower than the current that carries it) courtesy of a sea anchor, which essentially serves the same purpose as a parachute to a skydiver.

The Ocean Cleanup array relies on the relatively fast-moving plastic travelling in the ocean current to run into the slower moving barrier, causing it to become ‘trapped’. After enough trash has collected a ship or barge will have to motor out and remove all of the accumulated debris. This design is extremely bold and there are many skeptics in the ocean community who doubt the efficacy of this idea and think the millions of dollars in funding they’re received would be better spent elsewhere. Let’s look at the numbers.

Let’s Do the Numbers

I’m going to compare all these devices for ocean plastic pollution cleanup in terms of lifetime costs to their lifetime collection of debris. To keep things simple, I assume that all devices have equivalent operating lifetimes of ten years and I use a 4% discount rate on operating costs.

Mr. Trash Wheel’s Costs

Mr. Trash Wheel cost an estimated $850,000 to build and install and its average trash removal rate is about 200 tons of debris per year since May 2014 [9]. Someone has to empty the dumpster each time it gets full, which requires someone to transport the trash to a waste-to-energy facility where it is incinerated and the resulting heat is used to produce electricity. According to folks at the Baltimore Waterfront these operating costs average about $150,000 per year.

Seabin Costs

The Seabin costs about $4,050 per device and each removes approximately a half-ton of debris each year [2]. Operating costs are not available for this device, but we can make an educated guess. The Seabin uses power from the grid and someone needs to empty it periodically, which I estimate costs about $1,000 each year.

Ocean Cleanup Project Costs

Doing these same calculations for the Ocean Cleanup is a bit more challenging since the full scale device is not yet built, let alone operational. We can make an informed estimate though. The group’s prototype device cost about $1.35 million (1.1 million euro) [6], but this is only 100-meters-long or about 1/10th the size of the final design. Lets assume that build costs grow with prototype scale based on a log curve, not a linear one. For sake of discussion, I think it’s fair to say a full-scale device would cost about five times the cost of the prototype, or about $7 million.

The Ocean Cleanup team believes that their full-scale design will be able to collect 3 tons of debris per week [3], or about 156 tons per year. Since the device will be over a thousand nautical miles out, a ship or barge is needed to collect the trash and bring it back to shore for processing. They’ve estimated in their feasibility study that this would need to happen roughly every 45 days [5], or about eight trips each year. Charter rates for ships are notoriously expensive, on the order of $30,000 or more per day [8]. For a ship or barge to travel that far out, collect the accumulated trash, and return, would take about eight to ten days depending on vessel speed. This equates an operating cost of about $2 million each year for the Ocean Cleanup Device. We’ll be generous and assume that this includes maintenance costs for the device.

Plastic Revenue

The Ocean Cleanup Project actually has an opportunity to make some money from ocean plastic pollution by recycling the plastic they collect. This is possible for the Seabin device as well, but seems unlikely due to the small quantity being collected in each bin. For the sake of argument I’m going to assume that the Seabin group chooses to recycle the waste when possible as well. The Baltimore Waterfront Partnership would love to recycle the trash that they collect, but with the current infrastructure in place this would need to be done by hand and would be prohibitively expensive. However, future iterations of Mr. Trash Wheel in other parts of the world like southeast Asia will likely recycle.

Let’s assume that just Seabin and the Ocean Cleanup recycle the trash they collect and earn some revenue. It is difficult to estimate since different plastics have different values, but let’s use an average value of $0.50 per pound of recycled plastic, or $1,000 per ton [10]. I’m assuming that a generous 50% (by weight) of the debris that these devices collect each year is actually recyclable (probably an over estimate) and that the market values for plastic remain constant for the lifetime of the device.

Ocean Plastic Removal Cost Breakdown

The results of this number crunching are shown in the table below.

| Device | Location | Removal Rate (tons debris/year) | CAPEX ($’000) | OPEX ($’000) | Revenue ($’000) | NPV ($’000) | Cost per Ton ($/ton debris) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trash Wheel | Coastal | 205 | (850) | (150) | - | (2,070) | (1000) |

| Seabin | Coastal | 0.5 | (4) | (1) | 0.25 | (10.1) | (2000) |

| Ocean Cleanup | Offshore | 156 | (7,000) | (2,000) | 78 | (22,600) | (14,500) |

Discount rate: 4%

Operating Lifetime: 10

Price per pound of plastic: $0.50

Percent of Plastic Debris Recoverable: 50%

These numbers are indicative of why ocean plastic pollution is such a difficult problem. Upstream devices are cheaper than downstream, but all of these devices operate at a loss. If we assume that Mr. Trash Wheel can start recycling plastic and earn some revenue, it starts to look slightly more attractive in economic terms, but the other two are always a net loss for any realistic values. The critics of the Ocean Cleanup may have a point – the Trash Wheel collects 30% more debris each year for only 7% of the cost.

This quick and dirty economic analysis clearly misses some things. For instance, I’m not considering the benefits to ecosystem health, tourism, or any other industries that benefit from cleaner water. These would improve the financials, but they are incredibly hard to calculate. I’m also assuming that the amount of plastic collected each year remains constant. I want to believe that the amount collected each year drops as people become more conscious of their behavior, but the opposite is far more likely.

Moreover, once plastic is in the water it starts to breakdown into dangerous microplastics. The Ocean Cleanup and Mr. Trash Wheel groups are well aware of this, but their primary goal is to remove the plastic before it can break down into microplastics, not after. The Seabin is the only device of those I found capable of collecting these small bits of plastic, but they are deployed in ports and harbors where microplastics are less likely to be found.

Other Tools are Needed…

These devices are are not final solutions to ocean plastic pollution. Many argue, myself included, that once plastic reaches the water it’s already too late to mount any effective cleanup campaign. The numbers for the Ocean Cleanup Project are indicative of this: due to the distance from shore and low concentrations of debris spread over vast areas it’s much more costly to collect. But the plastic already in the ocean is not going away anytime soon and the Ocean Cleanup Project is the only group trying to change that.

These devices can be useful, but the best strategy is preventing plastics from entering the water in the first place. My next post will look further upstream at market and policy mechanisms that are being used to do just that.

Ocean Plastic Removal Tech Honorable Mentions

The concepts listed below are other pieces of tech that might be used to address the ocean plastic problem and are at varying levels of maturity.

- RanMarine’s Waste Shark – Autonomous surface vehicles for trash collection

- Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS) Plastic Collection Initiative – Repurposing Seismic Ships to Tow Long Nets

- Ocean Phoenix Project – Supersized Factory Ship Retrieving Ocean Plastic Waste

- OClean – Solar and ocean wave powered offshore litter collector

- Bluebird Electric – Ocean Enterprise 1, a marine autonomous robot to filter ocean water and remove plastics

References

[1] Snow, Jackie. “Googly-Eyed Trash Eaters May Clean a Harbor Near You”. National Geographic. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/02/mr-trash-wheels-professor-trash-wheels-baltimore-harbor-ocean-trash-pickup/

[2] The Sea Bin Project. http://seabinproject.com/the-product/

[3] The Ocean Cleanup. https://www.theoceancleanup.com/technology/

[4] Coburn, Jesse. “Fundraising nearly complete for Canton trash wheel”. The Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/features/green/blog/bs-md-ci-waterwheel-20160808-story.html

[5] Slat, Boyan et al. “How the Oceans Can Clean Themselves: A Feasibility Study”. 2014. https://www.theoceancleanup.com/fileadmin/media-archive/Documents/TOC_Feasibility_study_executive_summary_V2_0.pdf

[6] The Ocean Cleanup. “Annual Report 2016”. https://www.theoceancleanup.com/fileadmin/media-archive/Documents/TOC_2016_Annual_Report.pdf

[7] Thaler, Andrew. “Baltimore’s Garbage Wheel”. Hakai Magazine. 2015. https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/baltimores-garbage-wheel/

[8] Workboat. 2017 Day Rates. https://www.workboat.com/resources/reports/2016-day-rates/

[9] Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore. Trash Wheel Project. http://baltimorewaterfront.com/healthy-harbor/water-wheel/

[10] The Plastics Exchange. “Market Update”. http://www.theplasticsexchange.com/Research/WeeklyReview.aspx